The gut microbiome encompasses all microbial communities that reside along the entire 8-9 metres of the gastrointestinal tract. While research tends to focus on the microbes that reside in the lower gut, there is now growing interest in the microbes that reside in the upper gut and their implications on health. In fact, there is evidence that the mouth, oesophagus and small intestine harbour a diverse microbial community (Deo and Deshmukh 2019, Corning et al 2018, Kastl et al 2020).

Emerging research suggests the oesophageal microbiome (OM) may play a role in the development of oesophageal-related disease, although it remains unclear whether alterations in the OM causes oesophageal-related disease or whether oesophageal-related disease cause changes in the OM. Lifestyle factors influencing the OM include poor oral hygiene, smoking and diet.

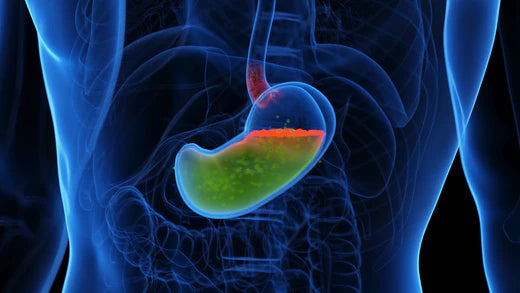

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders. In the Western world, GERD has been increasing over the last few decades, with a prevalence today of approximately 10-20%. GERD is considered an abnormal reflux response of gastroduodenal contents into the oesophagus with symptoms typically manifesting as heartburn, regurgitation, upper chest pain and/or nausea.

As with many gastrointestinal disorders, studies have shown an altered (or dysregulated) OM composition in those with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) compared with normal oesophageal tissue including higher levels of some Gram-negative genera, such as Campylobacter (Blackett et al 2013).

GERD and PPIs

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are typically the first-line therapeutic management of GERD, recommended for approximately 4-8 weeks (NICE 2019), though longer-term use is common. Since their introduction in 1989, PPI prescriptions have doubled in the UK and US. In fact, omeprazole makes up around four fifths of all PPI prescriptions.

Although PPIs are considered safe and well tolerated, with few adverse events reported, our understanding of the effects of longer-term PPI use on the microbial communities that span the entirety of the gastrointestinal tract is limited.

It is plausible that despite their clinical effectiveness in reducing symptoms of GERD via gastric acid suppression, PPIs may have less favourable effects such as further modifying an already altered OM by allowing survival of orally ingested microbes to colonise areas of the oesophagus.

PPIs and the gut microbiome

A systematic review of 19 studies including 12 observational studies (n=708) and 11 intervention studies (n=180) investigating the effects of PPIs found that although PPI treatment did not affect microbial richness or diversity, it was associated with distinct taxonomic alterations. For example, PPI users showed overgrowth of orally derived bacteria, such as Streptococcaceae. In stool samples, PPI use appears to increase multiple taxa at genus and family level (Macke et al 2020).

Another study that examined the effects of short and long-term PPIs on the upper and lower gut microbiome through collection of gastric mucosa biopsies and stool samples (16S rRNA sequencing) found distinct differences in abundance between PPI users and non-PPI users. For example, gastric mucosa sample analysis showed higher abundances of Planococcaceae, Oxalobacteraceae, and Sphingomonadaceae in the PPI group. In addition, the Methylophilus genus was more highly abundant in the long-term PPI user group than in the short-term PPI-user group (Shi et al 2018).

What’s more, analysis of stool samples showed significant compositional differences between PPI users and non-PPI users. For example, a higher abundance of Streptococcaceae, Veillonellaceae, Acidaminococcaceae, Micrococcaceae, and Flavobacteriaceae present in the PPI users compared with non-PPI-users (Shi et al 2018).

Equally, some studies have only observed small effects of PPI use on the OM (Deshpande et al 2018).

Collectively, these results suggest PPIs have the potential to alter the upper and lower gut microbiome. However, the clinical relevance of these compositional shifts remains unknown.

GERD and probiotics

While the use of probiotics for managing symptoms of GERD is mixed, a systematic review of 13 prospective studies (mixed study designs) reported some positive benefits such as improvements in heartburn and regurgitation. However, randomised controlled trials are warranted to confirm efficacy in alleviating GERD symptoms (Cheng and Ouwehand 2019).

Probiotics have a well-established safety profile. Based on evidence to date, there are no known contraindications if a patient wishes to trial alongside a PPI. However, it is important to manage expectations and communicate that the level of benefit is likely to be highly variable from person to person.